How Often Do You Lose a Baby Again After Uterus Ripping

- Research article

- Open up Access

- Published:

Maternal and fetal outcomes of uterine rupture and factors associated with maternal death secondary to uterine rupture

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 17, Commodity number:117 (2017) Cite this article

Abstract

Groundwork

Maternal bloodshed and morbidity are the priority agenda for sub-Saharan Africa including Ethiopia. Uterine rupture is the leading cause of maternal and fetal death in developing countries. Express evidence is available on the magnitude of uterine rupture; maternal and fetal outcomes of uterine rupture and factors associated with maternal decease secondary to uterine rupture in Ethiopia. This study aimed to assess the magnitude of uterine rupture; maternal and fetal upshot of uterine rupture and factors associated with maternal death secondary to uterine rupture in Debremarkos Referral Infirmary, Northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

An institutional-based cross-exclusive written report was conducted in Dec 2015 in Debremarkos referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. A full of 242 records of mothers with uterine rupture at Debremarkos referral Hospital during the twelvemonth 2011–2014 were included in the study. Secondary data was collected from the records of mothers admitted for the management of uterine rupture. Descriptive statistics were performed to characterize the study population. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to identify factors associated with maternal expiry secondary to uterine rupture. Odds ratio with 95% confidence interval was computed to determine the level of significance.

Results

A total of 10,379 deliveries were attended A total of 242 uterine rupture cases were included in this study. The magnitude of uterine rupture was ii.44% (one in 41 deliveries). Sixteen (6.half-dozen%) mothers died from uterine rupture. Xiv (v.8%) had experienced Vesico Vaginal Fistula. The bulk of the mothers, 72% (176), admitted for uterine rupture stayed in hospital for 6–ten days. Fetal upshot was grave, 98.3% (238) were stillborn. Identify of labor [Adjusted odds ratio (AOR): vi.92, 95% confidence interval (CI): (1.xvi, 33.74)], occurrence of hypo volume shock [AOR: iii.48, 95% CI: (one.01, 11.96)] and postoperative severe anemia [AOR: 0.092, 95% CI: (0.01, 0.956)] were significantly associated with maternal decease secondary to uterine rupture.

Conclusion

The magnitude of uterine rupture was high in the written report expanse. Initiation of labor at health institutions, early treatment of hypo-volumia and prevention of postoperative anemia is recommended to subtract maternal expiry secondary to uterine rupture.

Background

Uterine rupture is the fierce of the uterine wall and the loss of its integrity through breaching during pregnancy, delivery or immediately after delivery. Information technology is a catastrophic event in obstetrics, often resulting in both maternal and fetal adverse consequences. Across this, information technology may expose the women have harmful sequel such as permanently infertility secondary to hysterectomy [1].

Maternal mortality remains unacceptably loftier beyond many of the developing world specially in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and Southern asia. More than than 87% of maternal deaths from the global maternal bloodshed ratio of 210 deaths per 100, 000 live births in 2013 is deemed by Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia [two]. Federal democratic republic of ethiopia is the fifth country where the highest maternal bloodshed occurred side by side to Democratic Republic of Congo [3]. In this land, uterine rupture and obstructed labor together account for 29% of the full maternal mortality. This makes uterine rupture and obstructed labor to exist the second major causes of maternal mortality next to abortion-related complications [four].

Even though uterine rupture is a rare event in developed countries, information technology is nonetheless one of the major public health trouble in developing countries that endanger the life of many mothers [5]. WHO systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity secondary to uterine rupture showed that the prevalence of uterine rupture tends to be lower in developed countries than developing countries with a prevalence rate of 0.006%. Uterine rupture in developed countries by and large occurs secondary to prior cesarean section [1].

Globally, the incidence of uterine rupture is 0.07% which is much lower than what is in Africa - one.iii% [6]. The principal reasons for the occurrence of uterine rupture in developed countries are the apply of uterotonics and trial of labor on a scarred uterus [7–9].

However, the major causes of uterine rupture in developing countries are obstetric and non-obstetric multihued of factors such every bit; multi-gravidity, teen-historic period pregnancy, sometime primi, poor socio-economic condition, previous cesarean section scar, unsupervised labor and unwise use of uterotonic agents [ten]. A study from Republic of uganda reported that multi-gravidity, sometime historic period pregnancy, and rural residency as meaning predictors of uterine rupture [11]. In addition, studies from Nigeria and Uganda showed that the principal reasons for the occurrence of uterine rupture were unwise use of oxytocin drug, obstructed labor, 1000 multi-parity and abnormal fetal presentation [11–xiii].

A study conducted in Adigrat, Ethiopia showed that the causes of uterine rupture were cephalo - pelvic disproportion, mal-presentation, trial of instrumental delivery, unwise employ of Pitocin for consecration of labor and trial of labor with previous cesarean section scar. Uterine rupture maternal and fetal case fatality rate was 11.1% and 98.1% respectively [14].

The determinant factors for maternal consequence of uterine rupture differ beyond geographical boundaries due to the departure in socio-demographic status, and the availability and accessibility of skilled birth bellboy and health system effectiveness. Assessing maternal outcome of uterine rupture and factors associated with maternal death in the report area is important to design policies and strategies for the prevention and the clinical management of uterine rupture. Therefore, This study aimed at assessing the magnitude of uterine rupture; maternal and fetal outcome of uterine rupture and factors associated with maternal death secondary to uterine rupture in Debremarkos Referral Infirmary, Northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Report setting

Institutional based cross-sectional study was conducted in Dec 2015 at Debremarkos referral hospital. Debremarkos town is located 295 kilometers from Addis Ababa, the uppercase of Ethiopia. This hospital is ane of the referral hospitals in Amhara Regional Country and it potentially serves for more than than five million people of the East Gojjam Zone and four districts of the W Gojjam Zone. During the written report menstruum, ane Obstetrician, three Emergency surgical officers, one General practitioner, half dozen BSC and ten Diploma Midwives run the obstetrics and gynecology ward of the hospital. On average, the hospital conducts well-nigh three thousand deliveries annually.

Study population

For this study, all records of mothers with uterine rupture who delivered and managed at Debremarkos referral hospital during the year 2011–2014 were retrieved and included in the study.

Variable of the study

The result variables for this study were maternal outcomes, fetal outcomes and maternal expiry secondary to uterine rupture. Length of hospital stay, access related outcomes i.due east whether the mother admitted due to uterine rupture was improved and discharged from the hospital, maternal death and firsthand causes of maternal expiry were investigated. Fetal outcomes considered in this written report were stillbirth, live birth and whether the neonate was improved and discharged from the hospital. Due to numerous missing values, additional fetal outcomes such as Apgar scores and nascency weight were non included in our analysis.

We retrieved the charts of uterine rupture cases and collect independent variables such as socio-demographic characteristics (age, parity and place of residence), pregnancy and labor related variables (history of antenatal intendance, duration of labor, maternal vital signs, previous uterine scar, obstructed labor, and presence of hypovolemic daze during labor.) and treatment-related variables (claret transfusion, abdominal hysterectomy, and uterine repair). Maternal death secondary to uterine rupture was defined as death of the female parent from uterine rupture, its complication or management. We also nerveless data almost the presence of complete and incomplete uterine rupture, uterine scar, obstructed labor, consecration of labor, and augmentation of labor.

Information collection procedure

Kickoff, the records of mothers with a instance of uterine rupture managed at Debremarkos referral hospital from September 2011 to August 2014 were identified using their medical recording number from delivery and operation recording books. Vi diploma midwives were selected to collect the data and two BSC midwives were recruited for supervising the data collection process. After 254 charts were retrieved, data was collected using a structured and pretested questionnaire. This questionnaire was used but to larn data from the medical records. Data were so entered using EPI-INFO version iii.5.3 and exported to SPSS version 20 statistical software for farther analysis. Descriptive statistics were carried out to characterize the study population using different variables. Both bivariate and multiple logistic regressions were used to identify factors associated with maternal death secondary to uterine rupture. Variables having a p value of ≤ 0.ii in the bivariate analyses were fitted into a multiple logistic regression model to command the effects of confounding. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to declare the level of statistical significance in the multivariable logistic regression.

Results

A full of 10,379 deliveries were managed at Debremarkos referral hospital during January 1st, 2011 to December 30th, 2014. From this, 254 cases were admitted for uterine rupture.

Socio-demographic characteristics

Out of the 254 cases of uterine rupture, 242 (95%) charts of women were included in the analysis for this study. The remaining 12 cases of uterine rupture were discarded considering of incomplete, damaged and unreadable texts written from the charts.

More than half (56.6%) of the respondents were in the age group of 20–29. Two hundred seven (85.v%) of mothers with uterine rupture were from rural areas. Hundred fifty 3 (63.2%) of the mothers with uterine rupture had no history of ANC follow up. More than one-half of the respondents, 138 (57%) mothers started labor at home (Table 1).

Prevalence of uterine rupture

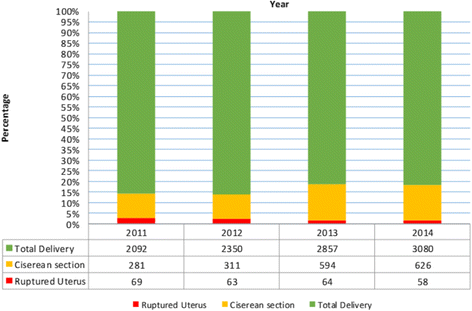

From a full of 10,379 deliveries during the study menstruation, 1812 (17.4%) of them were assisted by cesarean sections and 254 cases were uterine rupture with an overall prevalence rate of 2.44% or ane uterine rupture in 41 deliveries. The total number of deliveries and cesarean section charge per unit have increased considerably over the iv years period. Even so, the proportion of uterine rupture remained consistent (Fig. 1).

Annual numbers of deliveries, cesarean sections, uterine rupture percentages and uterine rupture: total delivery ratio at Debremarkos referral hospital from 2011-2014 (northward = 242)

Obstetric risk factors of mothers who faced uterine rupture

Amid the total of 242 cases of uterine rupture, 126 (52.1%) of mothers labored for longer than 24 h, 101 (41.7%) of the mothers labored for 12–24 h and fifteen(six.2%) mothers labored for eight–12 h. Eighty-nine (36.8%) mothers had no antenatal intendance follow up and 138 (57%) mothers started their labor at home. The majority, 216 (89.3%), of the mothers presented with obstructed labor, 9 (three.7%) mothers had history of consecration-augmentation, 9 (3.7%) mothers had previous history of uterine scar and eight (iii.three%) mothers had trial of instrumental commitment.

Preoperative clinical presentations of cases with uterine rupture

Two Hundred ix (86.4%) of mothers were diagnosed with uterine rupture preoperatively, 33 (13.6%) of cases were diagnosed intraoperatively. One hundred fourty-two (58.seven%) of mothers had abdominal pain and or tenderness, 148 (61.2%) had cessation of uterine contraction, and 177 (73.i%) didn't have fetal heart sounds, 102 (42.1%) mothers had multiple fetal palpable function, 83 (34.iii%) mothers presented with hypovolemic shock, and 37 (xv.3%) mothers came with vaginal bleeding. Ii hundred eighteen (90.1%) of mothers had preoperative HCT of ≥34, 17(7%) mothers had preoperative HCT value of 22–33% and 7(two.9%) mothers had preoperative HCT value of < 22%.

Intraoperative findings and surgical procedures of uterine rupture

During laparotomy, the majority of uterine rupture, 208 (86%) have a complete uterine rupture and 34(14%) had incomplete rupture. One hundred seventy-three (71.v%) of ruptures were inductive lower uterine segment, 43 (17.8%) cases were ruptured at the lateral segment and 26 (x.7%) cases had posterior segment rupture. Total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) was done for 138 (57%) of the cases, for 41 (xvi.9%) cases subtotal hysterectomy was performed, for 54(23.3%) cases uterine repair with bilateral tuba ligation (BTL) was done, for 9 (3.7%) cases uterine repair without BTL, for 56(23%) cases unilateral salphingo- oophorectomy was done and 24(9.nine%) cases had uterine rupture associated bladder rupture and repair was done.

Postoperative status of mothers managed for uterine rupture

One hundred 20-one (l%) of the cases had post-operative hematocrit value (HCT) of ≥34%, 68 (28.ane%) cases have HCT value of 22–33% and 53 (21.9%) cases have mail-operative HCT value of < 22%. Amidst those who take uterine rupture i hundred eighty-four (76%) of mothers had received blood transfusion. Amongst those who received claret transfusion 146 (79.three%) cases were treated with i unit of measurement of blood, 31 (16.viii%) cases received two units of blood, v(2.seven%) cases received three units of blood, one (0.5%) patient was treated with 4 units of claret and ane (0.5%) patients got 5 units of blood.

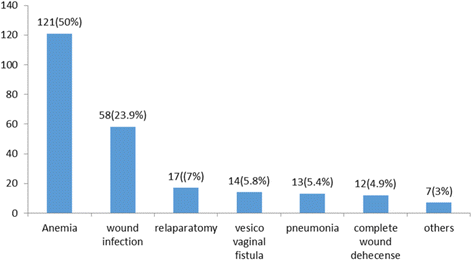

Postoperative complication of mothers who had uterine rupture

One hundred twoscore-nine (61.5%) of mothers managed for uterine rupture had developed postoperative complication. Of this, virtually of them (111 (48.5%)) had developed anemia and 17 (7%) cases had developed surgical site wound infection (Fig. 2).

Type and per centum of post-operative complication of uterine rupture at Debremarkos Referral Hospital, Northwest Federal democratic republic of ethiopia, from 2011–2014

Maternal outcomes of uterine rupture

Of the total of 242 mothers admitted for uterine rupture, 226 (93.iv%) were discharged and improved. Still, 16 (6.6%) of the mothers with uterine rupture died from different immediate causes of death: 6 mothers died from hypovolemic shock, 4 from severe anemia, 3 from septic shock, 1 from acute renal failure and 1 female parent from pulmonary edema. Ane hundred seventy-six (72%) of the mothers take stayed in the infirmary for 6–10 days and 44 (18.i%) of them stayed between 11 and 20 days in the hospital. Tragically, the perinatal outcomes were with grave consequences: 238 (98.3%) were stillbirths and simply iv(ane.7%) were live births. From the four live births, 2 were delivered through instrumental delivery, 1 from incomplete rupture, and i neonate was delivered from mother having previous cesarean section uterine scar dehiscence (CSD). Withal, for just one neonate, the discharge information was consummate. Information technology shows ane neonate was "improved and discharged from the hospital". As demonstrated in Fig. 3, maternal bloodshed has significantly declined from 2011 (669 per 100,000 live births) to 2014 (227 per 100,000 alive births) (Chi-foursquare for trend = 6.4, p-value = 0.01). More 35% (xiv out of 45) of the maternal deaths registered in Debre Markos Infirmary were due to uterine rupture. Moreover, there is no significant decline of maternal death attributed past uterine rupture during the period of 2011–2014.

Trend of Maternal Death Vs Expiry due to uterine rupture at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, 2011–2014

Factors associated with maternal death secondary to uterine rupture

Those mothers who had labored at home (AOR: 6.9, 95% CI: 1.16, 13.74), mothers with ruptured uterus who developed hypovolemic shock (AOR: three.48, 95% CI: 1.01, xi.96) and mothers with uterine rupture who have developed postoperative severe anemia (AOR: 0.092, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.956) were more likely to dice of uterine rupture in the multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Mothers with ruptured uterus who labored at home were more than likely to die than who labored at a health facility (AOR: half-dozen.ix, 95% CI: 1.16, xiii.74).

Those mothers with ruptured uterus who developed hypovolemic shock were more likely to dice than who did not developed hypovolemic shock afterward uterine rupture (AOR: iii.48, 95% CI: one.01, eleven.96).

Mothers with uterine rupture who did non adult postoperative anemia (postoperative HCT value of ≥ 22%) accept 91% less risk of death than those mothers with uterine ruptured who developed postoperative anemia (had postoperative HCT value of below 21%) (AOR: 0.092, 95%CI: 0.01, 0.956) (Table two).

Word

The prevalence of uterine rupture was plant to be 2.24% (one in 41 deliveries) in the report area. This finding is higher as compared to the studies from east and west Nigeria (0.4%) [12] and (one.two%) [13], Republic of ghana(i in 124) [fifteen], Turkey (i in 287) [8], Saudi Arabia (1 in 10011) [9], Nordic region (5.half dozen per 10 000) [16]. In addition, it is higher that the WHO systematic review for the causes of maternal mortality secondary to uterine rupture (0.053%) [5], Pakistan (0.41%) [17], Bangladesh (0.67%) [18] and North Westward Nigerian (0.61%) [xix]. This difference could be partly explained by the high prevalence of home delivery service (57%), socioeconomic and cultural differences across countries, availability and accessibility of skilled maternal care. Moreover, 85.5% of the mothers who suffered uterine rupture are from rural areas which limit the access to improved maternal intendance. Information technology was too higher when compared with the study in Adigrat hospital, Ethiopia (0.91%) [14]. This might be due to the improved medical documentation practice, demographic variation and low antenatal care service utilization in the study area.

Nonetheless, the prevalence in the electric current study was lower when compared with studies in Angola (4.nine%) [20] and Yergalem general hospital, Federal democratic republic of ethiopia (v%) [21]. This could be due to the time variation, improvement of health service infrastructure and quality of health service provision.

In this study, 57% (138) of the mothers labored at abode. This finding is consistent with the report in Adigrat hospital, Ethiopia [14]. The possible explanation could be due to lack of accessibility of adequate hospitals in rural parts of Ethiopia and lack of awareness of institutional commitment service utilization in most parts of the land [22].

Obstructed labor accounted for 89.3% (216) of uterine rupture in this study, while previous uterine scar accounted for only iii.7% (9) cases. This figure is much higher than studies from Nigeria, 47.3% (scar = 22.1%), Adigrat in the northern Ethiopia 79.six% (scar = 11.2%) and Pakistan 12.5% (scar = 12.5%) [12, 14, 17]. This deviation might be due to the variation in socio- economic factors and ecology factors, lack of transport for immediate shifting of patients to the referral hospital illiteracy in the customs, lack of antenatal care, lack of screening for high-chance pregnancy, and unsupervised labor conducted in poorly equipped centers. It might besides be due to the inadequacy of the health facilities to recognize and give definitive direction for Cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD) and obstructed labor.

The current report shows, the majority of uterine rupture, 208 (86%) take a complete uterine rupture and 34(14%) had incomplete rupture. Similar to this, finding, a written report from Turkey by Turgut and colleagues revealed that complete type of rupture is more likely to occur amidst mothers admitted for the management of uterine rupture [23]. Hysterectomy was performed for 73.9% of patients (Total Abdominal Hysterectomy = 57% (138) and Subtotal hysterectomy (STAH) =16.nine% (41)). For 27% of the cases, uterine repair (23.three% repair with BTL and for 3.7% repair without BTL) was performed. This finding is higher than studies from Turkey(TAH 0 34%) [23] and Nigeria, where hysterectomy was performed for 31.six% of cases (TAH =7.4% STAH = 24.2%) and repair without BTL was done for thirty% of cases of uterine rupture [24]. The possible explanation could be the difference in health intendance provider's skill and the difference in wellness institution prepare [25]. Ruptured uterus is the nearly common indication in performing hysterectomy [26–28]. Nonetheless, aberrant placentation was reported to be the virtually common indication for hysterectomy by a study from Turkey [8]. Although hysterectomy is considered as lifesaving process of obstetric emergency [26], it is invasive process [29]. Vaginal hysterectomy is rather minimally invasive and should exist the offset line of choice to consider earlier performing total hysterectomy [29]. If there is imminent uterine rupture around uterine fundal region, every bit Suhin and colleagues recommended, it might exist essential to consider alternative second-line strategies (such equally intrauterine balloon tamponade, uterine avenue embolization and compression sutures) to minimize blood loss and preserve uterus [thirty]. However, identifying the site of uterine rupture without performing laparotomy is challenging in medical practice.

Comparable hysterectomy rate was reported from Pakistan where hysterectomy was done for 76.6% (TAH = 26.half-dozen%, STAH = 50%) [17]. This might be due to the similarity in obstetrics causes of uterine rupture. Comparable proportions of obstetric chance factors such as obstructed labor, prolonged labor and previous history of uterine scar were reported in the Pakistani study [17].

Claret availability and transfusion in catastrophic situations of uterine rupture is a lifesaving cistron. As a upshot, this study shows 78% of the mothers who suffered from uterine rupture received claret transfusion which is comparable with the study conducted in Al-Batool Education Hospital, (83%) [7]. But in this written report, more patients were transfused when compared with the study in Adigrat and in Republic of yemen (57.1%), (59.iii%) respectively [14, 31]. This could be probably due to the poor hemodynamic state in which patients arrived in health institutions.

The electric current study shows 50% of cases developed anemia postoperatively. Out of these, severe anemia accounts for 21.9% of cases, but this finding is lower than the finding from Nigeria (93.seven%) [13]. The possible explanation might be due to the universal iron folate supplementation for all Ethiopian significant women past community health extension workers. Hence, this iron supplementation has a capacity to protect the occurrence of anemia subsequently delivery whatever its complication level of labor would be [32]. In add-on, depression level of hemoglobin is associated with mail service-partum hemorrhage [33].

In 9.nine% of the uterine rupture cases, there was associated bladder rupture which is comparable with a study from Yemen (8.6%) only lower than a report from Islamic republic of pakistan (21.1%) [x, 31]. Float rupture in association with uterine rupture reflects the presence of obstructed labor and belatedly presentation of mothers to the hospital [34].

In this study, fourteen cases (5.8%) developed vesico-vaginal fistula and 0.four% of cases developed recto-vaginal fistula. This finding is slightly college than the finding in Nigeria (four.ii%) and Yirgalem (iii%) [21, 24]. The possible explanation for this discrepancy could be due to the loftier occurrence of obstructed labor in this study and this is the main crusade of rupture. Only, the findings of uterine rupture in other studies may non be secondary to obstructed labor. The occurrence of bladder rupture and vesico-vaginal fistula advise nearly of the rupture cases were attributed by prolonged and obstructed labor and tardily presentation of mothers to the Hospital [5, seven].

All the same, the proportion of vesico-vaginal fistula in this study is lower than the finding from Adigrat study (12.five%) [14]. The possible explanation is the occurrence of high prevalence of obstructed labor in the report area in association with uterine rupture and there was an clan between bladder injury with obstructed labor [14].

From 2011 to 2014, 242 preventable cases of uterine rupture occurred in Debremarkos Hospital. Uterine rupture has been pointed out every bit a preventable tragedy of obstetric intendance in developing countries [35, 36]. It can, notwithstanding, tin be prevented by sustained dues-natal care institutional deliveries, early diagnosis, improved obstetric techniques [23, 34] and improving obstetric care to reduce the filibuster of women reaching obstetric clinics particularly for women with prolonged labor [35]. During the period betwixt 2011 and 2014, 45 maternal deaths occurred in the hospital, 16(half dozen.half-dozen%) of deaths include mothers managed for uterine rupture; this gave maternal mortality charge per unit of 35.five%. This figure is comparable to the findings in Pakistan 7.8% and in Yirgalem 6% [17, 21]. However, it is higher than a written report from Turkey (no maternal decease was recorded) [23]. This is due to the difference in the infrastructure of hospitals and wellness care provider's skill [25].

But, maternal bloodshed secondary to uterine rupture in this study was establish to be lower than the study from Angola (13.half-dozen%), and Adigrat (11.1%) [14, 20]. The possible explanation for this might be an earlier presentation of mothers to the infirmary set up, timely diagnosis of uterine rupture, adequate resuscitation of patients, availability of blood transfusion, absence of delay between diagnosis and definitive management and presence of experienced surgeon has outcome decrement of maternal expiry after uterine rupture.

In this written report, vi (37.five%) patients died from hypovolemic stupor, iv(25%) patients from severe anemia, 3 patients (18.vii) from septic shock, 1 patient (vi.3%) from acute renal failure and 1 patient (6.3%) from pulmonary edema. This figure is comparable to the study in People's republic of bangladesh where major causes of immediate death from uterine rupture were irreversible daze from astringent hemorrhage and septicemia [xviii].

In addition, 87.5% maternal deaths were among a mother who labored at dwelling house and was found to exist significantly associated with maternal death than laboring at a wellness facility. This study is similar to the report washed in Angola where maternal death was higher among mothers who labored at home and referred from primary health unit [twenty]. This can be explained by mothers being in a more unstable status are highly likely to dice.

Limitation of the report

Twelve charts of women managed for uterine rupture could not be retrieved or were incomplete. Hence, these charts were not included in the written report.

Determination

The magnitude of uterine rupture was loftier in the report area. Initiation of labor at home, the occurrence of hypo-volumia shock and occurrence of post-operative severe anemia were factors significantly associated with maternal decease secondary to uterine rupture. Early on diagnosis, well equipped Intensive Care Unit (ICU), good blood bank service, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of measurement (NICU), can help reduce maternal and perinatal bloodshed secondary to uterine rupture. In addition, initiation of labor in a health institution, early treatment of hypo-volumia and prevention of anemia is essential to decrease maternal death secondary to uterine rupture.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Ante natal care

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- BTL:

-

Bilateral tuba ligation

- COR:

-

Rough odds ratio

- CS:

-

Cesarean section

- FMOH:

-

Federal ministry building of health

- HCT:

-

Hematocrit

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- MMR:

-

Maternal mortality ratio

- NICU:

-

Neonatal intensive care unit

- SAH:

-

Subtotal abdominal hysterectomy

- SBAs:

-

Skill nativity attendants

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for social science

- TAH:

-

Total abdominal hysterectomy

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

-

Hofmeyr GJ, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM. WHO systematic review of maternal bloodshed and morbidity: the prevalence of uterine rupture. BJOG. 2005;112(nine):1221–8.

-

WHO. World health statistics 2014. Geneva: Switzerland World Health Organization; 2014.

-

WHO. Health status statistics: mortality. Geneva: World Wellness Organization; 2013.

-

Berhan Y, Berhan A. Causes of maternal mortality in Ethiopia: a significant decline in abortion related death. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2014;24(Suppl):fifteen–28.

-

Justus Hofmeyr G, Say L, Metin Gülmezoglu A. Systematic review: WHO systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity: the prevalence of uterine rupture. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112(nine):1221–8.

-

Guise J-M, McDonagh MS, Osterweil P, Nygren P, Chan BK, Helfand M. Systematic review of the incidence and consequences of uterine rupture in women with previous caesarean section. BMJ. 2004;329(7456):19.

-

Raida Muhammed A-W, Entessar Abdel A-J. Intrapartum Uterine Rupture. Mosul: Academy of Mosul; 2010.

-

Sahin HG, Kolusari A, Yildizhan R, Kurdoglu Grand, Adali E, Kamaci M. Uterine rupture: a twelve-year clinical analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21(vii):503–6.

-

Rouzi AA, Hawaswi AA, Aboalazm G, Hassanain F, Sindi O. Uterine rupture incidence, adventure factors, and outcome. Saudi Med J. 2003;24(i):37–nine.

-

Rizwan N, Abbasi RM, Uddin SF. Uterine rupture, frequency of cases and fetomaternal consequence. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61(4):322.

-

Mukasa PK, Kabakyenga J, Senkungu JK, Ngonzi J, Kyalimpa Thou, Roosmalen VJ. Uterine rupture in a teaching hospital in Mbarara, western Republic of uganda, unmatched case-control study. Reprod Health. 2013;x(i):one.

-

Eguzo KN, Umezurike CC. Rupture of unscarred uterus: a multi-year cantankerous-exclusive study from Nigerian Christian Infirmary, Nigeria. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2(4):657–60.

-

Omole-Ohonsi A, Attah R. Risk factors for ruptured uterus in a developing country. Gynecol Obstetric. 2011;one(102):2161–0932.1000102.

-

Gessessew A, Melese MM. Ruptured uterus-eight year retrospective analysis of causes and management event in Adigrat Hospital, Tigray Region, Federal democratic republic of ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2002;16(iii):241–five.

-

Fofie C, Baffoe P. A 2-year review of uterine rupture in a regional infirmary. Ghana Med J. 2010;44(3):98–102.

-

Colmorn LB, Petersen KB, Jakobsson Thousand, Lindqvist PG, Klungsoyr K, Kallen K, Bjarnadottir RI, Tapper AM, Bordahl PE, Gottvall M, et al. The Nordic Obstetric Surveillance Written report: a study of complete uterine rupture, abnormally invasive placenta, peripartum hysterectomy, and severe blood loss at delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(vii):734–44.

-

Qudsia Q, Akhtar Z, Kamran Thou, Khan AH. Woman health; uterus rupture, its complications and direction in teaching hospital bannu, pakistan. Maedica. 2012;7(1):49.

-

Khanam R, Khatun M. Ruptured Uterus: An Ongoing'Tragedyof Motherhood. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2001;27(2):43–7.

-

Adegbola O, Odeseye AK. Uterine rupture at Lagos University Teaching Hospital. J Clin Sci [serial online]. 2017;14:xiii-seven. Bachelor from: http://www.jcsjournal.org/text.asp?2017/xiv/1/13/199163. [cited 10 Apr 2017].

-

Strand R, Tumba P, Niekowal J, Bergström Due south. Audit of cases with uterine rupture: a process indicator of quality of obstetric care in Angola. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010;14(2):55–62.

-

McCauley Chiliad. Uterrine rupture in a rural hospital in Federal democratic republic of ethiopia, Yirgalem General Hospital, Yirgalem, SNNPR, Ethiopia, Global Women (GLOW) Conference, Nov 2013,Academy of Birmingham, p36. http://www.glowconference.org/uploads/3/1/8/5/31851337/collected_abstracts_2013.pdf. Accessed ten Apr 2016.

-

Shiferaw S, Spigt M, Godefrooij M, Melkamu Y, Tekie M. Why do women prefer home births in Ethiopia? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:5.

-

Turgut A, Ozler A, Siddik Evsen M, Ender Soydinc H, Yaman Goruk Northward, Karacor T, Gul T. Uterine rupture revisited: Predisposing factors, clinical features, direction and outcomes from a tertiary care center in Turkey. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29(3):753–vii.

-

Abasiattai AM, Umoiyoho AJ, Utuk NM, Inyang-Etoh EC, Asuquo E. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy in a tertiary hospital in southern Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;fifteen(60):one–15. doi: ten.11604/pamj.2013.15.sixty.1879.

-

Cisse CT, Faye EO, de Bernis L, Diadhiou F. Uterine rupture in Senegal. Epidemiology and quality of management. Med Trop (Mars). 2002;62(half dozen):619–22.

-

Nooren M, Nawal R. Obstetric hysterectomy: a life saving emergency. Indian J Med Sci. 2013;67(5-half-dozen):99–102.

-

Bassey G, Akani CI. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy in a depression resource setting: a 5-yr analysis. Niger J Med. 2014;23(2):170–five.

-

Ren GP, Wang BL, Wang YH. Measures of reducing obstetric emergencies hysterectomy incidence. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2016;29(2 Suppl):737–41.

-

Geller EJ. Vaginal hysterectomy: the original minimally invasive surgery. Minerva Ginecol. 2014;66(ane):23–33.

-

Sahin S, Guzin K, Eroglu M, Kayabasoglu F, Yasartekin MS. Respond to: letter to the editor entitled "Uterus preservation as an alternative to an emergency hysterectomy for postpartum hemorrhage". Curvation Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289(5):931–2.

-

Dhaifalah I, Santavy J, Fingerova H. Uterine rupture during pregnancy and delivery amid women attending the Al-Tthawra Hospital in Sana'a City Yemen Republic. Biomedical Papers. 2006;150(ii):279–83.

-

Khalafallah AA, Dennis AE. Fe deficiency anaemia in pregnancy and postpartum: pathophysiology and upshot of oral versus intravenous iron therapy. J Pregnancy. 2012;2012:630519.

-

Frass KA. Postpartum hemorrhage is related to the hemoglobin levels at labor: Observational report. Alexandria J Med. 2015;51(4):333–vii.

-

Fantu S, Segni H, Alemseged F. Incidence, causes and outcome of obstructed labor in jimma university specialized hospital. Ethiop J Wellness Sci. 2010;xx(3):145–51.

-

Mishra SK, Morris N, Uprety DK. Uterine rupture: preventable obstetric tragedies? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;46(6):541–five.

-

Prajapati P, Sheikh MI, R P. Case study rupture uterus: carelessness or negligence? J Indian Acad Forensic Med. 2012;34(i):82–5.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros would similar to forward our gratitude to the staffs of the Debremarkos Referal Infirmary medical records office and gynecology ward.

Funding

The authors did not receive funding for this written report.

Availability of data and materials

When ethical approving and permission letter of the alphabet was obtained from the medical director's function of the hospital, we accept agreed and signed not to publish the raw data retrieved from the medical records of the mothers. Notwithstanding, the datasets collected and analyzed for the current written report is bachelor from the corresponding author and can be obtained on a reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

GA initiated the idea, wrote the proposal; over sought the data collection, analyzed the data and drafted the paper. MA were involved in analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting the paper and reviewing it for important intellectual content. MK participated in the design and formulation, proposal evolution, reanalyzed the data, wrote the manuscript, revised the newspaper upon reviewers' comments, agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the piece of work in ensuring that questions related to the accurateness or integrity of any part of the piece of work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and canonical the terminal version of the manuscript.

Authors' data

GA: Section of Emergency Surgery, Higher of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Ethiopia

MA: Lecturer, Department of Midwifery, Higher of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Ethiopia.

MK: Lecturer, Institute of Public Wellness, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Ethiopia.

Doctoral boyfriend, Leibniz Establish for Prevention Research and Epidemiology – BIPS, Bremen, Frg

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approving and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethical Clearance Committee of the Establish of Health, University of Gondar. Ethical approval and permission letter to conduct the study in the obstetric gynecology ward was also obtained from the medical director'due south office of the Debremarkos Referral Hospital. To access the charts of mothers and retrieve relevant data, we received permission letter from the administration function of the hospital. Every bit this research was entirely based on secondary information, consent to participate was waived by the ideals committee. The questionnaire used to retrieve information from the medical records was not administered to patients. The administration office of the hospital also assessed our questionnaire to cheque that it should not include personal identifier questions.

We agreed to publish a summary of the information nerveless from the charts of the mothers. For the ease of retrieving and reviewing cards of patients, each medical record worker was adequately informed about the purpose and method of the study by the data collectors. After the relevant data was nerveless from the charts of mothers, charts were returned back to their original identify. Personal identifiers were not included in the written questionnaires to ensure participants' confidentiality.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give advisable credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and signal if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/cipher/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Nearly this article

Cite this commodity

Astatikie, G., Limenih, Chiliad.A. & Kebede, M. Maternal and fetal outcomes of uterine rupture and factors associated with maternal death secondary to uterine rupture. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17, 117 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1302-z

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1302-z

Keywords

- Ethiopia

- Maternal expiry

- Uterine rupture

- Ruptured uterus

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-017-1302-z

0 Response to "How Often Do You Lose a Baby Again After Uterus Ripping"

Post a Comment